Candle Craft 3: Two-Beat Structures

by Royal McGraw

Royal McGraw has written professionally for film, television, comics, and games for over 20 years. He led development on the mobile smash hit Choices: Stories You Play and currently serves as CEO of Candlelight Games.

Welcome! This is the third installment of a multi-part series intended to provide you with 10 Quick And Actionable Adjustments that you can make to your own writing process to improve your storytelling. Some of these process adjustments will be strategic, offering suggestions to improve how you think about storytelling from a big-picture standpoint. Some of these process adjustments will be tactical, offering suggestions to improve how you think about tackling scenes or even individual lines of dialogue. In all cases, these lessons have been hard-won, gleaned from over 20 years of experience writing across a variety of different mediums.

In the previous installment of Candle Craft, we explored two-beat storytelling. In practice, two-beat storytelling acknowledges that because stories are defined by the change they express, every scene in a story is inextricably entangled with (at least) one other scene.

Our first tip was: outline and write your scenes in pairs

This time, we’re going to build on that foundation and describe how to create practical two-beat structures.

What are Two-Beat Structures?

Last time, we looked at broad character arcs. We mapped the character journeys of Neo from The Matrix and Bella from Twilight into distinct beats – a beginning and an end. From that exercise, we can see that what we think of as a story is really the distance or journey between those two points. This measure of story is objective, and you can use it as a benchmark while you write.

This is the highest level two-beat storytelling, and it’s an important starting point. But diving a little deeper, we can see that the journey of a character through those two beats is rarely linear. Below that top-level structure are additional two-beat stories.

Think of the storytelling beats as atoms. Think of “change” as molecules formed by those beats. Two-beat structures are the substance created by a collection of those molecules.

All The World’s Stories

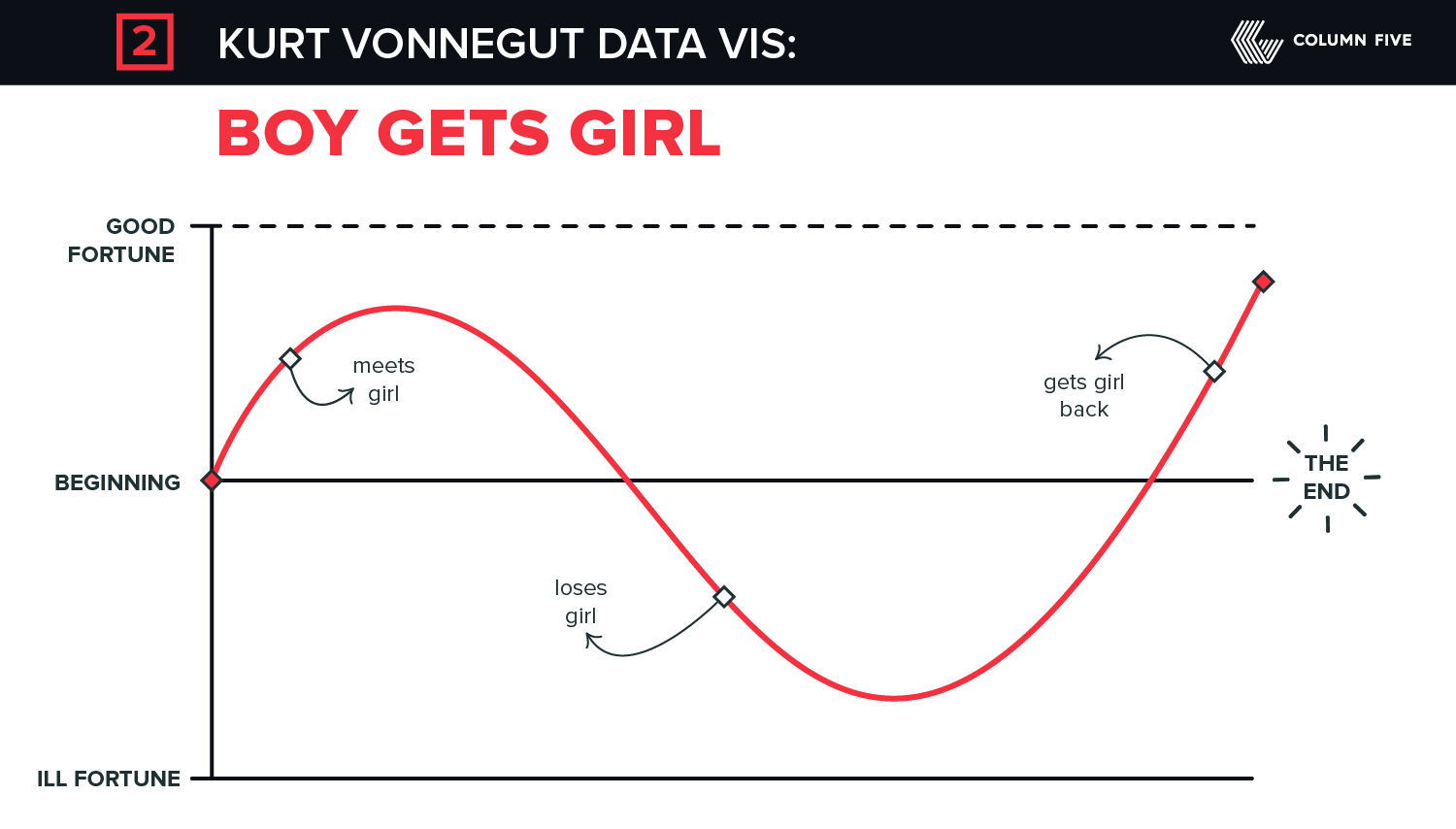

Kurt Vonnegut, author of classics such as Slaughterhouse-Five, attempted to create a unified thesis of storytelling around similar principles in A Man Without A Country. As part of this work, he hand-drew simple charts to describe what he felt were the key elements of all narratives, from fairy tales to blockbuster movies.

In his charts, Vonnegut placed good and ill-fortune on the vertical axis, and beginning to end of the story on the horizontal axis. After much research, he determined that there were five basic story forms:

Boy Meets Girl

Cinderella

From Bad to Worse

Good News/Bad News

Man in Hole

Now let’s isolate just one of these: Boy Meets Girl.

Setting aside a few quibbles around terminology* and the gendered naming conventions, what Vonnegut has done is mark out the emotional flow of Two-Beat Structures at the next level of detail.

Person Meets The Right Person

In the highest level two-beat structure, we have the most broad account of the story Vonnegut identified as Boy Gets Girl. Here, a person goes from being unhappily alone (or unhappily with the wrong person) to being happily together with the right person… or more plainly “Boy Gets Girl.”

Except, as the curve of the graph Vonnegut provided suggests, we have complications!

As we dig deeper, we see additional story beats appear. Now instead of just two beats, we have six beats. These beats connect across the narrative, moving from outside in. This view really helps us think about the increments of change that our characters undergo as they progress through the narrative.

In A1, our protagonist is unhappily alone (or with the wrong person).

In A2, our protagonist is happily together with the right person. To achieve this, our character must have solved for whatever made them unhappy. As a final reward, we see what their life will look like from now on.

What was the flaw in the initial status quo?

What does the new status quo look like after the flaw has been solved for?

How do their attitude change?

How does their attire reflect their attitude?

How do the locations they exist within change?

In B1, our protagonist meets the right person.

In B2, our protagonist gets back with the right person after the relationship falls apart. To achieve this, our protagonist must correctly identify the spark that initially made these two people perfect for each other.

What is that spark that makes the couple perfect together?

How does that spark manifest on a first meet?

How does that spark manifest when they decide to commit to each other for forever?

How do their attitudes change?

How does their attire reflect their attitude?

How do the locations they exist within change?

In C1, our protagonist initially commits to the right person.

In C2, our protagonist loses them. There is an error here – a misunderstanding of their own mind that causes the relationship to fall apart.

What is the false spark that makes the couple commit?

How might this show a glimpse of the culminating status quo?

How does the revelation of the false spark push the couple apart?

How might this revelation cause a retreat to the initial status quo?

How do their attitudes change?

How does their attire reflect their attitude?

How do the locations they exist within change?

As you can see, by mapping out the beats that form change in our story and connecting those beats as entangled pairs, we can begin to properly interrogate our characters, their interactions, and the world they exist in.

By answering these questions, we establish two scenes and the narrative contrast traveling between those states present to the audience.

This brings us to the next Quick and Actionable adjustment that you can make to own writing process to improve your storytelling:

TIP #2: Outline your narrative in two-beat structures to better interrogate what changes you need to demonstrate to your audience

Accept and acknowledge the reality that stories are composed of many entangled scene pairs, connecting to each other from outside in. Then leverage those two-beat structures to interrogate key elements of character development, attitude, attire, and place.

We’re going to talk about how to handle those key elements of character development in our next installment: UNDERMINE AND UNDERLINE.